Sweetness in Coffee: How Do We Define, Analyze and Discuss It?

This article was originally published in the March/April 2023 issue of Roast.

As you prepare for the upcoming workshop on sweetness in coffee at Roast Summit 2024, we encourage you to review this article written for Roast by our presenter Mike Ebert. This piece dives into the theory behind sweetness, one of the most sought-after qualities in coffee.

While the workshop will be focused on practical application, this article provides valuable context to help you approach the hands-on roasting exercises with a deeper understanding. For those looking for further insight, we recommend the Specialty Coffee Association’s Coffee Sensory and Cupping Handbook (published September 2021) for an in-depth look at sweetness perception.

Sweetness in Coffee: How Do We Define, Analyze and Discuss It?

By Mike Ebert

If you had one word to differentiate specialty coffee from commercial coffee, what word might you use? Special? Better? Tastier? I might suggest the word is—sweetness. Now, at some level, that is really dumbing it down. It’s much more complex than that, I believe, but it does work. Ted Lingle’s initial definition of specialty coffee in the early 1990s was uniform, clean and sweet, which are still core components for scoring coffee.

But how do we define or rate sweetness? When grading for the Coffee Quality Institute’s Q Program, it’s a pass/fail component. It’s either sweet or it’s not; there’s nothing related to intensity. In addition, we degrade 99 percent of the sugars present in green coffee during roasting, so why are we even talking about sweetness?

What we are talking about is the perception of sweetness. This perception comes from multiple influences; what’s in the green coffee itself, how that coffee is roasted, and how it is ultimately brewed brings out different aromas, tastes and textures. There is also the packaging of the coffee, the cup, and the environment. This area of research is somewhat new, and may seem subjective, but it’s not; it plays a huge role, and we need to take all of these aspects into consideration.

All our senses play a role. Think of eating an apple. How do color, weight, shape, firmness and juiciness play a role in your taste perception of it? Would your perception change if you knew it was bought from Aldi versus Whole Foods?

Sweet perception has been the focus of a lot of recent research. Reducing sugar content is a concern for the public and, therefore, major food manufacturers have invested heavily in research on sweet perception. Although the bulk of this research has not been focused on coffee specifically, it does give us some insight.

Some Highlights From Research on Sweet Perception

VISION—COLOR

Recent studies link color to specific tastes:

Red was associated with sweet tastes.

Yellow was associated with sour tastes.

White was associated with salty tastes.

Example: A latte was perceived to taste less sweet when served in a transparent glass cup with a white sleeve as compared to a blue sleeve or no sleeve at all.

VISION—SHAPE

Round shapes are perceived as sweeter.

Angular shapes are perceived as sour, bitter and salty.

Example: Round-shaped chocolates were perceived to taste sweeter and less bitter than angular shaped chocolates.

HEARING

Sounds of chewing contribute to the perception of crispness and freshness.

Example: If the sound of biting into an apple is dulled by background noise, it won’t be perceived as being as fresh as if the sound were not dulled.

This particular area has not been studied to see if sweetness is affected, but ambient sounds (loud versus quiet background noise) can also influence taste perception. Sweet foods were rated lower in sweetness when loud background noise was present.

Example: Smart food packaging; “sonic sweetener” in ready-to-drink (RTD) coffee to deliver sweet or bitter sounding music as its consumed.

OLFACTION

Aromas such as caramel, vanilla and berry flavors have been found to increase the perception of sweetness.

The catch: Previous exposure is key and can differ for people from different cultural backgrounds. Everyone perceives flavor and aroma differently.

TASTE

Taste interactions are not well understood, partly because of contradictory results. However, some things have been found to alter perceptions.

Salt: The perception of sweetness was increased with low levels of salt, for instance, but no change was noted with higher levels.

Bitterness: Medium to high levels seem to suppress sweetness.

Umami and its effect on sweetness has not been studied.

ORAL SOMATOSENSORIAL (MOUTHFEEL)

There is some evidence that increased viscosity (body) can reduce taste perception in sweet solutions, as well as other flavors.

Temperature of a beverage plays a role as well: Temperatures in the 70 to 80 degree F range were found to result in the highest perception of sweetness, as well as bitterness, saltiness and sourness. In some people, rapid heating increased sweetness.

PACKAGING

The texture and shape of packaging also plays a role. In one study, biscuits taken from a plate that was smooth were found to be sweeter but less crunchy than those taken from a rough plate. In another, hot chocolate and coffee were served in two different cups. The drinks served in cups with rounded surface patterns tasted sweeter than those served in more angular-cut cups.

Confused? What does this all mean? We are still learning many things about how we perceive smell and taste. But we can piece together findings that can assist us in coffee roasting.

For a deeper read on sweet perception and the research noted in this column, read the Specialty Coffee Association’s Coffee Sensory and Cupping Handbook, published in September 2021.

Coffee is a complex beverage. The bottom line is that multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence our perception of flavor—including sweetness. We must remember that it’s all about the proper modulations of these interactions to bring balance to the cup, and in specialty coffee, sweetness should always be present!

Let’s explore the variables that are found in the coffee itself—both the green we start with and the roasted coffee, based on the roast profile we choose.

GREEN COFFEE

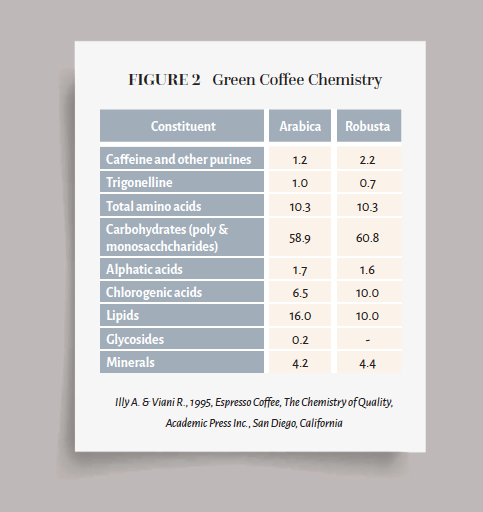

From Figure 1, we can see green coffee is made up of roughly 30 to 40 percent carbohydrates, 10 to 12 percent protein, 10 to 13 percent oils and lipids, 4 to 5 percent acids, 10 to 13 percent water, 4 percent of various nutrients and 0.5 to 2.5 percent alkaloids (caffeine). These vary depending on species, soil, processing method and other factors. You can see the differences in the chemical makeup of arabica and robusta coffee in Figure 2.

Another factor, and perhaps the greatest in regard to sweet perception, is elevation. Figure 3 shows the amount of caffeine, caffeoylquinic acids (CQA) and nicotinic acid in green and roasted coffee. In short, it shows lower amounts of these in higher-grown coffees. Lower amounts of these would increase sweet perception.

PROCESSING

Post-harvest processing plays a role as well. You are probably already familiar with washed (parchment dried), natural (fruit dried), pulped natural (honey) and wet hulled (seed dried, giling basah). These methods all change the overall sugar content and the percentage of each type of sugar in coffee. See Figure 4 for how they differ.

ROASTING

Coffee roasting plays an important role, too. Some 800 to 1,000 different aroma compounds have been identified in roasted coffee. These compounds are all products of:

Maillard reactions

Strecker degradations

Amino acid breakdown Degradation of trigonelline Chlorogenic acids (CGA) degradation Degradation of phenols Degradation of sugars

Oxidation of lipids

The interaction of all of the above

Figure 5 shows the difference between green coffee chemistry and roasted coffee chemistry. In general, most would agree that if you roast:

LIGHT in color you will:

Maximize the acidity Minimize bitterness Produce fruity/floral aromas

MEDIUM in color you will:

Produce a medium acidity (between light and dark roasts)

Produce medium bitterness (between light and dark roasts)

Produce caramelized aromas

DARK in color you will:

Maximize the bitterness

Minimize acidity

Create strong roast aromas

Ultimately, it’s all about balancing the sweet, sour and bitter, the perception of which are driven by the intrinsic and extrinsic factors at play. But also understand there are different modalities of sweetness:

Light roast: Sweet/Sour

Medium Roast: Sugar Browning

Dark Roast: Sweet/Bitter

Over the past two years, I have presented this information as a class at the annual Specialty Coffee Expo, and every month during my company’s roasting classes. We have blind cuppings on these various modalities, and the results were not exactly as I expected.

For the first tasting, we had a low-grown versus a high-grown Guatemalan. This flight was the only one in which the results matched my expectations: The high-grown was perceived as sweeter by 95 percent of the participants.

The next flight was a parchment dried (washed) versus a fruit dried (natural). This one surprised me, for I figured most would perceive the fruit that can be found in naturals as sweeter. While the results did lean this way, it wasn’t as much as I anticipated: Only 55 percent found the fruit-dried sweeter.

The final flight included light, medium and dark roasts of a Costa Rican washed coffee. I had expected most people to find either the light roast (sweet/sour) or the medium roast (caramel, vanilla, chocolate) sweeter, but that was not at all the case. It was split pretty evenly among the three.

As I mentioned, we have done this multiple times in the past two years, and the results have been similar each time. We have stuck with the same coffees, roast profiles, etc. We used the standard 1:16 brew ratio and Behmor brewers. We handed out samples in white cups, with three-digit codes. Participants wore red glasses, and no talking was allowed until the tasting was complete. We then tallied the results and discussed.

This is not to say that all similar roast profiles bring out the same sweetness; not at all. Too short of a roast, or short development time, can lead to vegetal or pea pod type flavors, as well as pronounced sourness. Mike Perry, an award-winning roaster out of Rancho Cucamonga, California, says, “We find by extending the beginning of the development phase, the time in first crack, we can create a sweeter, more balanced cup that people do prefer, both professional cuppers and the general public.”

Adequate time is needed to properly develop those sugar-browning flavors associated with sweetness. However, too long of a time can mute brightness, which will decrease sweet perception. As Perry says, “It’s not just the roast color, but the profile to get there that matters.”

“Sweetness in specialty coffee, I have to agree, is quite complex to understand and takes a bit of work to sort out on the palate—and lots of trial and error to roast,” says Karen Weckerly of Coroco Coffee in Sycamore, Illinois. “Taking the SCA sensory class at the Coffee Roasters Guild Retreat prior to opening my business was invaluable to me. In my experience, I found it initially challenging to zero in on sweetness on my palate. In addition to cupping frequently, I actually found great opportunities to train myself simply doing quality control on the espresso shots in my cafes. What I found was that I had to really differentiate between acidity and bitterness to be able to taste the sweetness in the balance. Having that sensory foundation helps me train my team and maintain high standards for roasted coffee, as well espresso drinks created in my cafes.”

We all perceive sweetness differently, and many factors influence this perception. As roasters, we seek to create balance between sweet, sour and bitter, largely through green coffee selection and roasting methods. By exploring research related to flavor perception, we may be able to expand our influence even further.

MIKE EBERT is founder of Firedancer Coffee Consultants, dedicated to helping clients create a personalized strategy to ensure long-term success. He works primarily with roasters, producers and retailers, drawing from his extensive experience in all facets of the specialty coffee supply chain to guide clients in reaching their potential. Ebert is an Authorized SCA Trainer (AST) for the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA); a certified preventive control qualified individual (PCQI); and lead trainer for food safety. He co-chairs curriculum for the SCA Educational Advisory Council, which develops new educational experiences for the specialty coffee community.

Advertisement